The Jurassic King of Scotland

Last week, a [paper] was published that described a new fossil of a previously known mammaliaform from Scotland. This animal is called Wareolestes rex, meaning Ware’s brigand King and it’s from the middle Jurassic Period (specifically the Bathonian, 168 to 166 million years ago). Mammaliaforms were starting to diversify in the middle Jurassic, and were relatively small, so finding any fossils of them is important to our understanding of how they lived.

A reconstruction of Wareolestes by E. Panciroli.

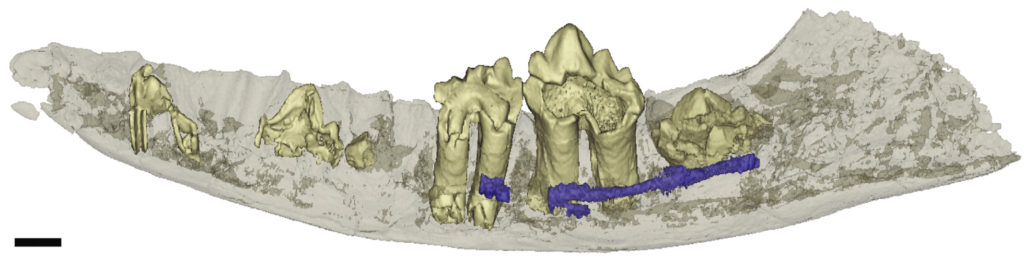

The new specimen of Wareolestes is a lower jaw with teeth. This fossil was CT scanned and the details of the teeth were recreated with computer software. The authors found that the jaw had two molars preserved in place, and several teeth that were hiding in the bone, waiting to erupt.

Figure 4 from the paper showing the CT scan of the jaw. The large molars are already erupted, but several premolars and another molar are still in the jaw. The purple is the mandibular nerve. The scale is 1mm.

The original fossil of Wareolestes is an isolated molar, but similarities with the molars preserved in this new specimen show that the two specimens come from the same species. The shape of the teeth indicate that Wareolestes is a morgonucodontan (an early mammal relative).

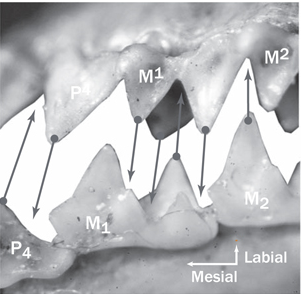

The un-erupted teeth show that Wareolestes replaced their teeth once in life. Most mammals have a set of baby teeth (also called ‘Milk’ teeth) and a set of adult teeth. This happens for two main reasons: 1) our mouths grow over time, but teeth cannot grow once they are formed, so we grow adult teeth to fit adult-sized mouths. And 2) our teeth fit precisely together so that we can chew our food really well (this is called precise occlusion), by only replacing our teeth once, we ensure that our teeth will fit together appropriately.

A photo showing how the different cusps of the premolars (labeled P4, for premolar 4) and the molars (labeled M1 and M2 for molar 1 and 2) fit together. From P.D. Polly.

By comparison, other animals (like crocodiles, for example), do not have a final adult size – they grow continuously as they age. They also replace their teeth as many times as they need to ensure they always have teeth for grabbing prey, but they don’t chew like mammals do, so their teeth don’t have to fit together.

This new specimen shows that morganucodontans had a similar tooth replacement pattern as modern mammals, and are the most basal mammaliaforms that have it.