She Sells Sea Shells by the Sea Shore

This week, I’m going to tell you about Mary Anning, the first well-known woman paleontologist, and the one whose story inspired “She Sells Sea Shells by the Sea Shore”.

Mary was born in 1799 in Lyme Regis, England, which is a coastal town. The coast by Lyme Regis has a cliff with rocks from the Jurassic Period (around 200 million years ago).

Map of Lyme Regis, England.

When Mary was 15-months old she was struck by lightning and survived, leading the townspeople to think of her as a miracle child. She learned to read and write at her local school, but beyond that her education was very limited.

She lived with her parents, Richard and Molly, and older brother, Joseph. Her father made furniture and supplemented their income by going to the coast to find fossils, which he would sell to tourists. He often brought Joseph and Mary with him to find fossils along the beach. When her father died in 1810, Mary continued to hunt for fossils to provide money for her family. Together with her brother, Mary found the skeleton of an ichthyosaur on the beach. They sold it and eventually it ended up in the British Museum.

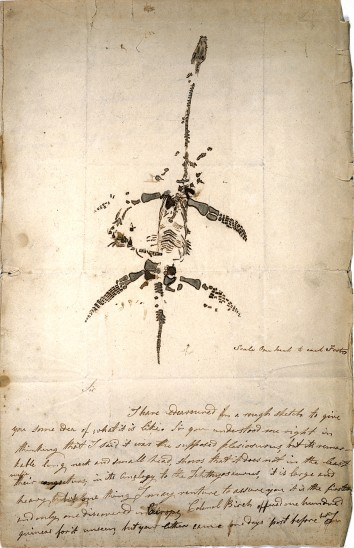

The ichthyosaur that Joseph and Mary Anning discovered as children.

Mary would go down to the beach with her dog, Tray, and look for ammonites, belemnites, vertebrae and other fossils. She’d take them home and clean them up, and in the afternoons, she’d sell her finds by the town road.

A portrait of Mary with her dog, Tray.

Eventually she made enough to open her own shop. Her finds were so good that they attracted the attention of known scientists. She found the first British specimen of a pterosaur and the first complete plesiosaur. She dissected modern squids and fish in order to better understand the animals she was finding.

Mary’s illustration and notes on the plesiosaur she discovered.

Even though she was not allowed to join the new Geological Society of London (no women were allowed to join at that time), many of her finds and research was presented there through the men she’d sell her fossils to. Often, they would not credit her at all. As her reputation grew, her scientist friends started adopting her ideas more readily. However, times were often tough for Mary, as it was hard for her to earn money. Her geologist friends, Henry de la Beche and William Buckland helped her through these moments. William even convinced the British Association for the Advancement of Science to provide her with an annual pension for her impressive work.

Mary died of breast cancer at a young age in 1847, but had a tremendous impact on paleontology. Because of her, we know that the stones in the guts of ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs are actually fossilized feces (called cololites).

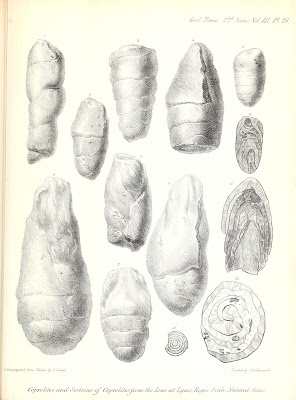

Cololites are feces preserved in the body. Coprolites, depicted here by William Buckland (1835), are feces preserved outside the body.

Mary started with very little in life, and even though she had only a few years of formal education, she worked every day to learn something new, find more fossils, and share her work with others.