Back from the Field

I’m back from a wonderful trip to the Hanksville Dinosaur Quarry in Hanskville, Utah. This excursion is led by the Burpee Museum of Rockford, Illinois, a spectacular regional Natural History Museum known for its top notch research collections and amazing exhibits. I’ll talk about the day to day activities, and how we find and extract fossils in quarries.

Day to Day:

The day started at 8 am with a delicious breakfast prepared by the local restaurant, Blondies. We then headed back to basecamp to get all of our gear for the day, fill up the coolers with ice water and lunches, and head in to the quarry. It was about a 20-minute drive to get there, mostly on a county road with amazing rock exposures.

By the time we got to the quarry, temperatures would be reaching the high 90s°F. We would work until around 12:30, and break for lunch under the break tent. We worked until around 3:30 when temperatures peaked (highest was about 104°F) and a break was needed.

You can see the blue tent behind the cars.

Work continued until 5 or 5:30, then we packed up and headed to the base for showers, dinner, and an evening activity. Sometimes that was checking out a state park, like Goblin Valley State Park. Sometimes we’d wait until dark and go look at the stars.

Goblin Valley State Park

Extracting Fossils

Extracting fossils from a quarry is not something I had done before. They used these tools called an ME-910, which is basically a mini-jackhammer. It hammers away the rock little by little so you can find hidden bone and safely remove the rock around it.

Once the fossil is found, we take away the rock around it, leaving it on a little pedestal of rock. We don’t ever want to completely remove the bone from the rock because the bone can easily break. Leaving it encased in rock keeps it stable until we can get it back to a museum for further preparation.

Next, the bone (a dinosaur chevron) is ready for plaster! I love this part because it’s like an arts and crafts project. First you cover the bone in wet paper towels to protect it from the plaster. Then it gets a layer of tin foil. Then we use burlap and plaster to cover it up.

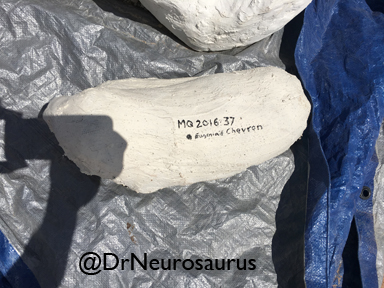

The plaster jacket gets a field number and label, and is mapped in the quarry so the collections manager can know exactly where in the rock that bone came from.

Mapping the location of the bone.

Finished jacket with field number.

Next time I’ll talk about how we prospect (look for fossils in new places), about the wildlife we saw, and I’ll share some photos of the amazing geology.